Platforms and The President

Apr 25, 2025

I recently wrote a paper for my university course–awarded distinction–on the subversion of state power by platform technologies and how this shift reshapes international hierarchy. In it, I argued that platforms increasingly resemble feudal lords: the decentralised nature of the internet enables platform executives to rule their digital domains with minimal interference from traditional institutions. But a recent Foreign Affairs article by Farrell and Newman has significantly changed my thinking. (1)

Like many others, I’ve long viewed advancements in information technology as a check on government power. Broadly speaking, government authority thrives when information flows are centralised—when data travels to a central hub and “truth” is distributed from that centre. (2) The internet, by decentralising information, seemed to undermine this model. Yet over the past decade, platform companies have grown acutely aware of their influence as a small set of digital gatekeepers. Despite the illusion of decentralisation, these networks are internally centralised: nothing you see on social media comes directly from another user but is instead filtered through the platform’s central processing mechanism—the algorithm.

As these firms became more aware of their power, they began to engage in politics, hoping to secure a more favourable business environment through regulatory and tax advantages. This strategy hit its peak between November 4th, 2024, and April 2nd, 2025—a time when many believed that Silicon Valley’s alliance with President Donald Trump would yield long-term rewards. But on "Liberation Day" (April 2nd, 2025), that optimism collapsed. The perceived value created during those five months evaporated almost overnight. (3)

Now, attention has turned to how the world might respond to Trump’s emergent tariff regime.

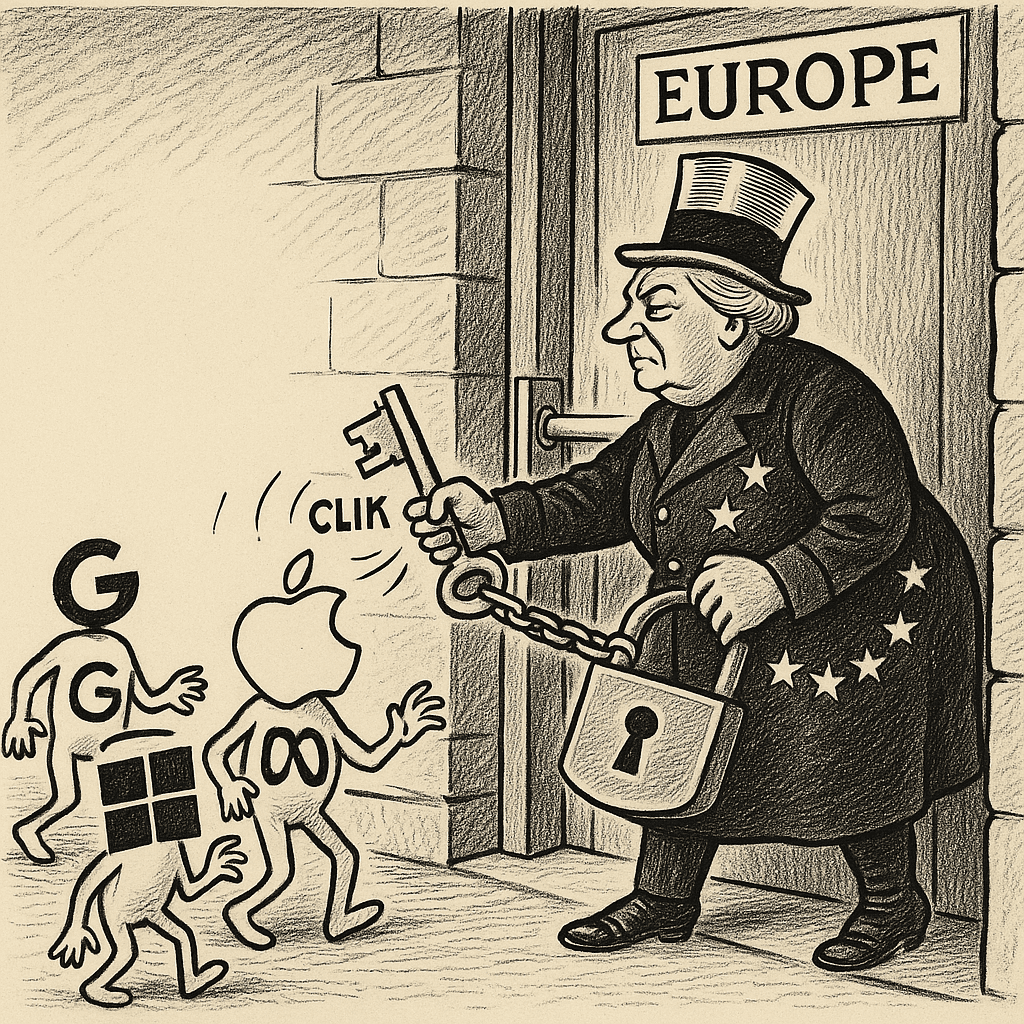

Although the U.S. is a net importer of goods, it is also a major exporter of services–particularly digital and financial services, which are in high demand globally. (4) This gives service-importing countries, especially the EU, a powerful tool: the ability to retaliate by taxing or suspending access to American digital services, potentially gaining leverage in trade negotiations. The EU, as a unified reading bloc and a net importer of U.S. services, is uniquely positioned to wield this option. If the EU chooses to retaliate through the services channel, many platforms could find themselves effectively locked out of the European economy, at least temporarily. This scenario challenges the assumption that improved information technology necessarily diffuses power. In this case, governments are actively curbing the reach of digital networks, reasserting control and reshaping the balance.

None of this is especially revolutionary thinking, as these conversations are already happening both in Silicon Valley boardrooms and in public discourse. But it raises a deeper question: When–if ever–does the power of platforms surpass that of the state?

For now, platforms remain subject to government control because they are, fundamentally, entities rooted in the physical world, which states have spent millennia learning how to govern. Corporations are made up of people, and those people live in physical bodies, subject to the laws of the places where they reside.

But that physical vulnerability may not last. As algorithms increasingly manage platforms, especially in content curation, the possibility arises that future algorithms will also take over management roles, running entire operations without human intervention. This is one plausible pathway through which advanced AI could come to “conquer the world”: not through physical domination, which AI is ill-suited for, but through domination of the digital realm.

Humans are inherently limited in their ability to centralise and process the vast flows of information moving through the internet. But AI is not. A sufficiently advanced AI could manage this data flow effortlessly, potentially making the internet navigable only with AI assistance—and, in turn, consolidating digital power in unprecedented ways.

Farrell, H., & Newman, A. (2025, April 3). The Brewing Transatlantic Tech War. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/brewing-transatlantic-tech-war

Harari, Y.N. (2024) Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI. New York: Random House.

International Services (Expanded Detail) | U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). (2023). Bea.gov. https://www.bea.gov/data/intl-trade-investment/international-services-expanded

Wigglesworth, R. (2025). Wall Street analysts anguish over ‘Liberation Day’. [online] @FinancialTimes. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/f5df7652-c3db-4332-8b29-7037d9f74180.

(Photo credit @DALL-E 2025)